Effectiveness of 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Acts

- SEIC

- Dec 29, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 10, 2023

Authors: Joel Tan, Ivan Chin

Region Head: Ace Chua

Editor: Akshat Daga

Abstract

On 22 December 2017, Trump signed the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) and promised it would boost economic growth by 1.7%, increase repatriation of foreign earnings, increase employment by an equivalent of 339,000 full time jobs and wages of workers by 1.5%. In doing so, the TCJA cut individual personal income tax rates and slashed corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%, the lowest rates since 1939. Additionally, the TCJA shifted from a worldwide tax system where individuals are taxed on their worldwide income regardless of where the income was derived to a territorial tax system where firms or individuals are not taxed on foreign profits to boost domestic investment (Trostorff & Wilson, 2017). This article seeks to analyse the efficacy of the 2017 TCJA in living up to Trump’s promises particularly in the aspects of employment, investment and consumption. Recommendations that the US administration could have undertaken were also suggested.

Introduction

The 2017 TCJA was highly regressive in nature. The TCJA cut individual personal income tax rates, among which the top marginal tax rate for the highest income earners dropped by a substantial 2.7% from 39.6% in 2017 to 37% in 2018 (fig.1 ). Personal income tax cuts accrued to the higher income individuals were substantially higher than that for the lower income earners. Coupled with the high corporate tax cuts of 14%, much of the TCJA benefits can be seen as being concentrated in the hands of the higher income earners, especially if the higher ups of firms do not pass down these cost savings to workers.

Fig.1 Personal Income Tax Cuts Rates

Investment

Fig.2 firm’s desired capital stock

To maximise profits, firms will produce up to the point where MPKf = (user cost) / (1- t).

According to Fig.2, theory suggests that a decrease in the effective tax rates from corporate tax cuts will decrease the tax-adjusted user capital cost from UC1 to UC2, which increases the desired capital stock of the firm from K1* to K2* and increase investment of firms to maximise their profits.

Fig.3 business investment

However, in reality, capital stock growth was stagnant, business investments decreased and even turned negative in 2019 after the TCJA was enacted (fig.3). While repatriated profits amounted to $664 billion, firms did not invest in the expansion of their capital stock but instead bought $1 trillion worth of stock buybacks. The uncertain economic outlook from the rising US-China trade tensions also dampened investors’ confidence which may have contributed to the lacklustre investment growth.

Employment

Fig.4 Labour market diagram

Theory suggests that a cut in effective tax rates lowers tax-adjusted user capital cost which increases the capital stock of firms, resulting in the MPN increasing. As such, labour demand shifts from ND1 to ND2, increasing employment from N1 to N2 and boosting wages from W1 to W2 (fig.4).

Fig.5 U.S. Unemployment rates

However, the reality was that job growth was relatively steady and largely unaffected by the 2017 TCJA. The number of new jobs gained in the immediate months after the tax cuts were quite similar to the previous years. According to fig,5, while unemployment decreased slightly to 3.5%, it was lower than the rate of decrease during Obama’s Administration. It was unlikely that the tax cuts had any significant effects on increasing employment. In fact, according to the National Association for Business Economics, 84% of firms did not increase their hiring due to the tax cuts (Hanlon, 2020).

Fig.6 Changes in wages and GDP

The TCJA also had limited effect in boosting wages with workers receiving only marginal benefits. Only 15% of tax cuts were accrued to employees with bonuses amounting to just an average of $28 per employee while 60% of the tax cuts were concentrated in the hands of the shareholders (Mahedy, 2019). According to fig.6, the TCJA did not increase the wages of workers, with wages dipping in Q2 of 2018 before re-bouncing back to the initial levels pre-TCJA act.

Much of the inefficacy of the TCJA boils down to investors not spending the tax cut incentives on labour but instead on corporate stock buyback to increase their shares of the company since many investors believed that their corporate stocks were undervalued and that they can reap the highest bang for the buck in buying these stocks back from the marketplace with the tax cut incentives.

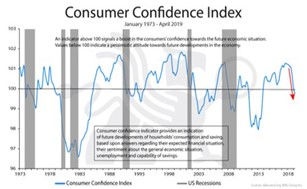

Fig.7 Corporate Stock Buybacks Fig.8 Consumer Confidence Index

Fig.8 Consumer Confidence Index

After the TCJA was enacted in 2017, corporate stock buybacks soared from about $80 billion to a whopping $175 billion in 2018 (fig.7). Amidst the 2018 US-China trade tensions, confidence index also fell below 100, indicating that many investors were largely pessimistic of the economy, which hindered them from utilising their TCJA incentives to invest in the expansion of their capital stocks (fig.8). As such, less than 20% of firms increased profits from the tax cuts were spent on capital expenditure (IMF, 2017).

Consumption

Fig.9 US private consumption expenditure of GDP

In terms of consumption, the TCJA had limited effect in increasing consumption. Private consumption only increased by a sluggish 0.46% of nominal GDP from July to Oct 2018 (fig.9) , indicating the possibility of Ricardian Equivalence holding to a certain extent. Consumers could have expected taxes to rise in the future, which led to their lifetime wealth not increasing significantly and this ultimately had limited effect on their consumption. Another possibility could be the TCJA were largely regressive, the lower and middle income earners were unlikely to reap substantial tax cut benefits compared to the higher income earners who enjoyed significant tax incentives. As a result, since most of the tax incentives fell to corporations and the high income earners who generally have significantly lower marginal propensity to consume (MPC), the changes in their disposable income were unlikely to increase their consumption significantly.

Debt

Fig.10 U.S. Debt-to-GDP ratios

Prior to the TCJA, the U.S. was already ridden in debt. After the implementation of the 2017 TCJA which costs $5.5 trillion worth of tax cuts, the debt-to-GDP ratio of the U.S. will spike to 111% by 2027, relative to the 89% of debt-to-GDP ratio without the tax cuts according to CBO projections. (fig.10). The worsening of the U.S. fiscal position will render them vulnerable to using fiscal stimulations to boost the economy in recession especially when the country is already in a huge debt.

Policy Recommendations

Firstly, the U.S. should have focused on increasing productivity of the economy. According to the Solow model, ongoing productivity growth can lead to continuing improvement in output and consumption per worker. Building human capital to enhance quality of workforce, and Research & Development contributes directly to growth. As such, excessive red tape to increase entrepreneurial activities can be removed; financial incentives should be given to R&D and to encourage workers to constantly upgrade their skills to maintain a competitive domestic labour force so as to attract FDI.

In terms of the TCJA, the administration can consider making the cuts more progressive rather than regressive in nature by ensuring lower income households get a bigger share of the pie. For example, tax cuts in more regressive taxes such as consumption and sales taxes so that lower income households with higher MPC can increase their consumption. The provision of higher personal income tax cuts for the lower income households can also contribute to this.

With US debt projected to hit 16% of GDP and about $3.3 trillion in 2020, which is unprecedented since World War II, due to years of steadily increasing debt and emergency spending in response to the COVID-19, the US should consider increasing taxes on high income earners instead and look at increasing taxes in areas with negative externalities, such as the implementation of carbon taxes to improve their fiscal position.

Conclusion

Prima facie evidence thus far suggests that the 2017 Tax Cut & Jobs Act is overpromising and under-delivering, especially with limited effects on economic growth and the widening of income inequality due to the regressive tax cuts. However, naysayers will suggest the idea of a time lag, but it is unlikely that the proposed goals of the TJCA will be met given the rising global uncertainties from COVID-19, US presidential election and US-China relations.

References

1.Setty, G. (2019, December 5). US lost more tax revenue than any other developed country in 2018 due to Trump tax cuts, new report says. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/12/05/us-tax-revenue-dropped-sharply-due-to-trump-tax-cuts-report.html

2.Hanlon, G. (2020, January 31). The TCJA 2 Years Later: Corporations, Not Workers, Are the Big Winners. Retrieved December 02, 2020, from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2019/12/19/478924/tcja-2-years-later-corporations-not-workers-big-winners/

3.Trostorff, A. T., & Wilson, B. T. (2017, February 1). Worldwide Tax System vs. Territorial Tax System. Retrieved from https://www.natlawreview.com/article/worldwide-tax-system-vs-territorial-tax-system#:~:text=In a pure worldwide tax, the residence of the taxpayer.

4.Katzeff, P. (2019, March 28). How The New Trump Tax Brackets Impact Your Tax Rate. Retrieved from https://www.investors.com/etfs-and-funds/personal-finance/how-tax-reform-impacts-your-tax-bracket-and-rate/

5.Amadeo, K. (2020, January 18). How Trump's Tax Reform Plan Affects You. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/trump-s-tax-plan-how-it-affects-you-4113968

6.Frazee, G. (2019, January 28). Did Trump’s tax cuts boost hiring? Most companies say no. PBS NewsHour. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/making-sense/did-trumps-tax-cuts-boost-hiring-most-companies-say-no

7.Egan, M. (2018, February 16). Tax cut scoreboard: Workers $6 billion; Shareholders: $171 billion. CNNMoney. https://money.cnn.com/2018/02/16/investing/stock-buybacks-tax-law-bonuses/index.html

8.Kopp, E. (2019). US Investments Since Tax Cut and Jobs Act 2017. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WP/2019/WPIEA2019120.ashx

9.Pomerleau, K. (2020, July 31). The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Retrieved November 7, 2020, from https://taxfoundation.org/treatment-foreign-profits-tax-cuts-jobs-act/

10.Howard, G. (2020, February 5). Despite Trump’s Claims, It Is Hard To See Much Economic Impact Two Years After Passage Of The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2020/02/05/despite-trumps-claims-it-is-hard-to-see-much-economic-impact-two-years-after-passage-of-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/?sh=7f1906c97237

11.Knott, A. M. (2019, February 19). Why The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act (TCJA) Led To Buybacks Rather Than Investment. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/annemarieknott/2019/02/21/why-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-tcja-led-to-buybacks-rather-than-investment/?sh=42c22da437fb

12.Hendricks, G. (2019, September 26). Trump's Corporate Tax Cut Is Not Trickling Down. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2019/09/26/475083/trumps-corporate-tax-cut-not-trickling/

13.McBride, J., Chatzky, A., & Siripurapu, A. (2020, September 9). The National Debt Dilemma. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/national-debt-dilemma

14.Gale, W., & K. (2019, June 4). How to Reduce the National Debt -- With Bipartisan Support. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/how-to-reduce-the-national-debt-with-bipartisan-support/

15.Mahedy, T. (n.d.). Retrieved December 02, 2020, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-06/trump-s-big-tax-cuts-did-little-to-boost-economic-growth

-cutout.png)

Comments